Clusterfrock - ClusterFrock

More Posts from Clusterfrock and Others

Elizabethan Jewelry Chains

Let’s talk Elizabethan shiny things!

Left: Portrait of a Nobelwoman in a cartwheel ruff, attributed to John Bettes the Younger, 1585 Right: Portrait of a Lady Aged 21, Unknown Artist, c.1590

Specifically, I want to talk about jewelry chains. They were often worn just like necklaces, but they were also draped around the shoulders or draped in loops at the front of the bodice. They could be extremely long – one found in the Cheapside Hoard was 8 feet long!

These chains are featured heavily in portraiture from the 16th and 17th centuries, and thanks to the Cheapside Hoard, we have quite a few extant examples of these jewelry chains.

The Cheapside Hoard was found during the demolition of a house near St. Paul’s Cathedral, back in 1912. As they broke through the floorboards of the house and into the much older basement, they discovered a cache of over 500 pieces of late Elizabethan and early Stuart-era jewelry. The jewels featured emeralds from Columbia, diamonds and rubies from India and Burma, ancient Egyptian and Byzantine jewels and coins, as well as delicate gold and enamelwork crafted by the goldsmiths in London. At the time, Cheapside was London’s main shopping center and the home to the majority of the goldsmiths. It’s thought that the hoard was buried to keep it safe, possibly during the English Civil War.

I set out on a hunt to find jewelry bits that resembled the links we see in the Cheapside Hoard pieces. Amazingly, I came across some suitable pieces on AliExpress!

Left: Chain from AliExpress Right: Detail of Cheapside Hoard chain, Museum of London

I didn’t set out to copy any one chain from the Hoard, but instead used the shapes and sizes of those chains to help guide me while I was buying my bits and pieces.

Finding the suitable pieces was really the most difficult part of making these chains. Once everything arrived, assembly was quick and simple.

I ended up with quite a variety of finished chains. None of them are as long as their cousins in the museums, but I think they’re a good start to my Elizabethan jewelry collection, and will definitely grace the front of many a bodice at future events.

Bibliography:

Cheapside Hoard Chains, London Museum —Enameled Chain of Flowers, Bows, and Leaves https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/v/object-119591/enamelled-chain-of-flowers-bows-and-leaves/ —Enameled Floral Chain https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/v/object-119585/enamelled-floral-chain/ —Diamond and Enamel Chain https://www.londonmuseum.org.uk/collections/v/object-119584/diamond-and-enamel-chain/

Cheapside Hoard Chian, V&A Museum —Chain, 1590-1620 https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O74076/cheapside-hoard-chain-unknown/

Forsyth, H. (2013). London’s Lost Jewels: The Cheapside Hoard. Philip Wilson Publishers.

Wheeler, R. M. (1928). The Cheapside Hoard of Elizabethan and Jacobean Jewelry. Antiquity: A Review of World Archaeology, 2(8). https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/abs/the-cheapside-hoard-of-elizabethan-and-jacobean-jewellery-by-r-e-mortimer-wheeler-london-museum-catalogues-no-2-1928-1s/1E585E583A88D8B55DB29EE30B85D79E

Ganoksin. (2016, October 19). The Cheapside Hoard – Ganoksin jewelry making community. https://www.ganoksin.com/article/the-cheapside-hoard/

Hackenbroch, Y. (1941). A jewelled necklace in the British Museum. The Antiquaries Journal, 21(4), 342–344. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003581500048381 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquaries-journal/article/abs/jewelled-necklace-in-the-british-museum/965C70079702E42C7096519CBF7A8470

Was sifting through some late 16th/early 17th century stammbucher (basically little scrapbooks that people would collect cards, stamps, drawings, etc in, especially while travelling; their friends and family could also add little entries to your book, like memories, poems, drawings, or well wishes) in online libraries, and thought I'd share some fun images of people doing who knows what. Bowling for ladies? Running from cupid and getting tied to trees for it? Rolling around your really bendy dude? Just another Tuesday in 17th century Germany.

by threadhandedjill

A New Crinoline and 1850s Petticoats

Finally getting around to posting about my new 1850s undies! I finished them last winter, but Life happened, so here I am, a year and a half later.

Anyway, I finished a new crinoline and basic cotton petticoat first. The crinoline was made by first making the lower section out of cotton muslin, and attaching twill tape at even intervals. I then made each bone individually, the casing made from twill tape, then the boning threaded through, and then the bone stitched closed at the needed circumference. I played around with the size of each bone before I stitched it to the tapes to get the overall shape that I wanted.

To go over it, I made my standard cotton petticoat with a single flounce.

Then I actually got around to reading period descriptions and suggestions for petticoats in fashion magazines of the time, and found that they frequently recommended petticoats made of grosgrain fabric, with three flounces from the knee to the hem. So, I searched the internet and finally found some grosgrain fabric, which I had to order from Greece. (Spoiler alert - grosgrain and faille are pretty much indistinguishable, which I wish I'd known before because faille is way easier to find.)

Anyway, the construction of the petticoat was not difficult, but the grosgrain fabric was a nightmare. It frayed at the slightest touch, exploding into a thousand tiny shards. My serger was garbage and not working, so I used a side cutter presser foot instead, which sort of acts as a serger. It definitely helped, but by the time I discovered said presser foot, I was already so over this project that I threw it in the naughty corner for months because I couldn't stand to work on it anymore. I finally dug it out a few months later and finished it up.

I have to say, it does give an enormous amount of floof, but I would never, ever recommend making one to anyone else. It was a nightmare from start to finish.

There's a more detailed writeup with more of my petticoat research and in-progress photos on my main blog, so please do check it out!

I do not knit, but I have seriously considered learning how, exclusively so I could make one of these.

We have a surprising number of these knitted jackets in museums, most of them of Italian origin, most likely from Naples or Venice. According to the V&A, it seems that they were made in workshops as individual panels that were sold as sets that could be sewn together at home. I'm partial to the green and gold ones, like this one from the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Knitted Jacket

1600s-1690s

Italy

Knitted silk jackets were fashionable in the early 17th century as informal dress. This example is very finely knit by hand in plain silk yarn and silk partially wrapped in silver thread, in contrasting colours of blue and yellow. Characteristic of this style of jacket, it has a border of basket weave stitch and an abstract floral design worked in stocking and reverse stocking stitches. The pattern imitates the designs seen in woven silk textiles. The jacket is finely finished with the sleeves lined in silk and completed with knitted cuffs. Along each centre front, a narrow strip of linen covered in blue silk has been added, with button holes and passementerie buttons, worked in silver thread. The provenance of the jacket indicates that it is probably Italian.

Victoria & Albert Museum (Accession number: 473-1893)

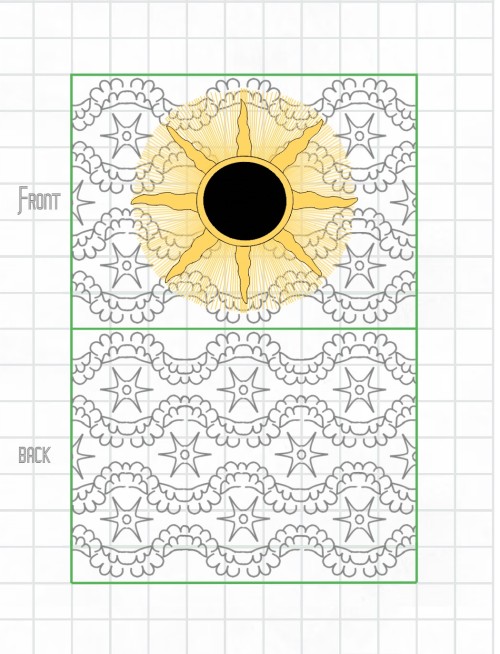

Had a last minute notion to make an Elizabethan-inspired embroidery pattern to celebrate the eclipse. I originally thought of doing a coif pattern, but thought the eclipse would get lost in the folds of the cap, so I ultimately went with a sweet bag. Since it was cloudy throughout totality, I thought it would be fun to incorporate the stars & clouds embroidery from a c.1600 waistcoat at the Bath Fashion Museum. The sun design is inspired by various period illustrations of sun motifs, minus the face they always seemed to put on every sun/moon design because I just couldn't make it not look silly.

I have no idea what stitches I would use for this bag, since sweet bags tend to use all sorts of different stitches. The original stars & clouds design is in blackwork, but I haven't seen any evidence of blackwork used on sweet bags. I'd probably do the background in a black or darkest blue metallic gobelin stitch (also ahistorical, but pretty!), the clouds/stars in silver stem stitch, the corona and rays in satin stitch or plaited braid, and the moon in black detatched buttonhole or some other fill stitch. Or I'd do the entire thing in blackwork except the corona and rays of the sun, which I'd do in gilt, documentation be damned.

Le Bon Ton, Journal de modes. September 1854, v. 37, plate 7. Digital Collections of the Los Angeles Public Library

One of my favorites. Still planning to make my green version someday.

yellow silk evening dress with oak leaf design

c.1902

House of Worth

Fashion Museum of Bath

Hello, Stripes, you have my attention. ♥

La Mode: revue du monde élégant. Troisième année. Juillet. 1831. Paris. Pl. 166. Robes de Mousseline blanche et mousseline à raies brochées, façon de Melle Palmire. Coiffures de M. Hypolite — Bijoux de Chauffert, Palais royal. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Stripes, my beloved, I see you there.

Revue de la Mode, Gazette de la Famille, dimanche 26 septembre 1886, 15e Année, No. 769

Print maker: A. Chaillot; Printer: P. Faivre; Paris

Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Netherlands

Keep reading

-

b1ueman liked this · 6 days ago

b1ueman liked this · 6 days ago -

jaydenyte liked this · 1 week ago

jaydenyte liked this · 1 week ago -

southerncountrygentleman-2 liked this · 1 week ago

southerncountrygentleman-2 liked this · 1 week ago -

cone-and-green-tablecloth reblogged this · 1 week ago

cone-and-green-tablecloth reblogged this · 1 week ago -

satedanfire reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

satedanfire reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

satedanfire liked this · 2 weeks ago

satedanfire liked this · 2 weeks ago -

thedeadarts liked this · 2 weeks ago

thedeadarts liked this · 2 weeks ago -

crookedlylovinggoatee69 reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

crookedlylovinggoatee69 reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

crookedlylovinggoatee69 liked this · 2 weeks ago

crookedlylovinggoatee69 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

crookedlylovinggoatee69 reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

crookedlylovinggoatee69 reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

bed-rotting reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

bed-rotting reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

scottish-eejit liked this · 2 weeks ago

scottish-eejit liked this · 2 weeks ago -

notascurious liked this · 2 weeks ago

notascurious liked this · 2 weeks ago -

darkpatrolwolf liked this · 2 weeks ago

darkpatrolwolf liked this · 2 weeks ago -

feartheshadowsofnight reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

feartheshadowsofnight reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

feartheshadowsofnight liked this · 2 weeks ago

feartheshadowsofnight liked this · 2 weeks ago -

theunwantedwife reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

theunwantedwife reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

reservedkinkgrl liked this · 2 weeks ago

reservedkinkgrl liked this · 2 weeks ago -

gr8-2sh reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

gr8-2sh reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

gr8-2sh liked this · 2 weeks ago

gr8-2sh liked this · 2 weeks ago -

cyrxtmblr liked this · 2 weeks ago

cyrxtmblr liked this · 2 weeks ago -

dewildegurl1313 liked this · 2 weeks ago

dewildegurl1313 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

silverbeardmtnman reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

silverbeardmtnman reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

downydatura liked this · 2 weeks ago

downydatura liked this · 2 weeks ago -

oliviartist liked this · 3 weeks ago

oliviartist liked this · 3 weeks ago -

oliviartist reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

oliviartist reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

ijustasideblog liked this · 1 month ago

ijustasideblog liked this · 1 month ago -

destroyinglonely liked this · 1 month ago

destroyinglonely liked this · 1 month ago -

aurora-boreali liked this · 1 month ago

aurora-boreali liked this · 1 month ago -

nezzs-reblog-addiction reblogged this · 1 month ago

nezzs-reblog-addiction reblogged this · 1 month ago -

wildernezz liked this · 1 month ago

wildernezz liked this · 1 month ago -

cumberbatchedandproud reblogged this · 1 month ago

cumberbatchedandproud reblogged this · 1 month ago -

glitchwitchx reblogged this · 1 month ago

glitchwitchx reblogged this · 1 month ago -

darthbloodorange reblogged this · 1 month ago

darthbloodorange reblogged this · 1 month ago -

cabinet-of-crafts liked this · 1 month ago

cabinet-of-crafts liked this · 1 month ago -

liquidlightning reblogged this · 1 month ago

liquidlightning reblogged this · 1 month ago -

fuckingfangtastic reblogged this · 2 months ago

fuckingfangtastic reblogged this · 2 months ago -

dreams-child reblogged this · 2 months ago

dreams-child reblogged this · 2 months ago -

dia-oro reblogged this · 2 months ago

dia-oro reblogged this · 2 months ago -

porfinmor liked this · 2 months ago

porfinmor liked this · 2 months ago -

emmajanereading reblogged this · 2 months ago

emmajanereading reblogged this · 2 months ago -

angrycrabeyes liked this · 2 months ago

angrycrabeyes liked this · 2 months ago -

airmidcelt reblogged this · 2 months ago

airmidcelt reblogged this · 2 months ago -

skin-bible reblogged this · 2 months ago

skin-bible reblogged this · 2 months ago -

mybikesurly liked this · 2 months ago

mybikesurly liked this · 2 months ago -

pedarr-pedarrrr liked this · 2 months ago

pedarr-pedarrrr liked this · 2 months ago -

unoeil liked this · 2 months ago

unoeil liked this · 2 months ago -

ratven0m reblogged this · 2 months ago

ratven0m reblogged this · 2 months ago