Check Out This Little Guy And Support The Artist!

Check out this little guy and support the artist!

11/14/19 Dacentrurus. The meaning of the name of this member of Stegosauria from the late Jurassic is “Tail Full of Points”. So…a pin cushion (ask your mom or grandmother). #sonjebovember #drawdinovember2019 #dinosaur #dacentrurus #sewing #pincushion #artistsoninstagram #animaldrawing #cuteanimals https://www.instagram.com/p/B422vRLjr2s/?igshid=1euzgg4cxscgd

More Posts from Violetdawn001 and Others

What is an Artfight?

Something to have fun with!

Thank you, Cupcakeshakesnake, for giving me permission to use your designs of Lurien the Watcher and his butler! The end results looks amazing!

P.S.

If you want to check out LittleSnaketail's work, here are links to the artist's profiles!

DeviantArt: Here

Tumblr: Here

Well, forget about a bestiary for Christmas. I should invest in a sea animal encyclopedia!

The Lancetfish is a species that looks like it comes straight out of a realistic fantasy world building project.

Please, feel free to write any WatcherDad Aus for Hollow Knight.

reblog if you’re okay with people writing fanfics of your fanfics and/or fanfics inspired by your fanfics

Thank you so much OP for doing all this work. It makes attempting to draw Hollow Knight a lot easier.

you've probably seen this before, or made the connection yourself (ignore bottom right corner)

but there's also this:

The flowers of the Queen, the crown of the King, and the Hollow Knight

Sometimes...a little Humble Pie like this allows one to create the most beautiful masterpieces.

Now excuse me while I go create. Don't you have something to create too...Artist? Writer? Go while you still have time. I hope to see you again with flushed cheeks and starry eyes as you show me your latest creation.

being an artist is humiliating

I don't think this is talked about enough.

When you put something out in the world, you have to accept the possibility you won't get anything back.

Maybe you laid your heart bare on a one-shot that got zero comments. Maybe it was a painting you spent hours working on that didn't get the engagement you wanted.

I think it might have been the reason I stopped creating, for a little while at least.

I got obsessed with the stupid little numbers and metrics. Got happy when people liked my content, got sad when it resonated with no one. My relationship with what I created was determined by my perception of how many people engaged with it.

I waited day and night for the dopamine rush of notifications. I refresh my inbox, thinking that one of these days, somebody will leave some kind of affirmation, and somehow that recognition will imbue what I created with more significance. More value, writ-large.

If it got crickets, then I've failed somehow. It just wasn't good enough, I say to myself.

For the longest time, I felt like everything I created had to prove it belonged. It all felt like a race, except I didn’t know who I was competing against, only that I always felt left behind and couldn't keep up.

That's my fault. I can't help but measure myself.

But isn’t that the universal tendency? To view our past achievements as a benchmark we have to constantly overcome? Isn’t that why we’re so satisfied to look at old works we made and see how far we’ve come?

I remember what my old teacher used to say. “You’re only as good as your last piece.” As if art exists only to constantly prove itself. As if art is forever doomed to fight for its place in this world.

Well, I'm sick of it.

And so I'm realizing, in real-time, that I don’t want to fight for my place anymore. I don’t want to pander to some stupid algorithm.

I want to create.

I want to believe that a work of art is good simply because it exists out of necessity. Out of someone’s urgent desire to share a piece of their heart in the world because it would have been devastating to keep to themselves. That’s always been very beautiful to me. It's why there is so much heart in fanworks because of the sheer heart poured into it—a love that is as raw as an exposed nerve.

There are so many stories in your head, numerous in number and nebulous in form, that eventually come to fruition as these delicate, precious things you’ve been brave enough to summon into existence. To materialize in a timeline or dashboard. To somehow take up space in people’s minds if only briefly.

Maybe that in itself is the miracle. That what you conjured in your head somehow made its way into something real. Whether in tiny strokes or tiny letters on a tiny screen.

Somehow, the numbers next to them don’t seem to matter as much.

@livyamel

You can write that fainting competition now where your opponent is Dante!

The Anatomy of Passing Out: When, Why, and How to Write It

Passing out, or syncope, is a loss of consciousness that can play a pivotal role in storytelling, adding drama, suspense, or emotional weight to a scene. Whether it’s due to injury, fear, or exhaustion, the act of fainting can instantly shift the stakes in your story.

But how do you write it convincingly? How do you ensure it’s not overly dramatic or medically inaccurate? In this guide, I’ll walk you through the causes, stages, and aftermath of passing out. By the end, you’ll be able to craft a vivid, realistic fainting scene that enhances your narrative without feeling clichéd or contrived.

2. Common Causes of Passing Out

Characters faint for a variety of reasons, and understanding the common causes can help you decide when and why your character might lose consciousness. Below are the major categories that can lead to fainting, each with their own narrative implications.

Physical Causes

Blood Loss: A sudden drop in blood volume from a wound can cause fainting as the body struggles to maintain circulation and oxygen delivery to the brain.

Dehydration: When the body doesn’t have enough fluids, blood pressure can plummet, leading to dizziness and fainting.

Low Blood Pressure (Hypotension): Characters with chronic low blood pressure may faint after standing up too quickly, due to insufficient blood reaching the brain.

Intense Pain: The body can shut down in response to severe pain, leading to fainting as a protective mechanism.

Heatstroke: Extreme heat can cause the body to overheat, resulting in dehydration and loss of consciousness.

Psychological Causes

Emotional Trauma or Shock: Intense fear, grief, or surprise can trigger a fainting episode, as the brain becomes overwhelmed.

Panic Attacks: The hyperventilation and increased heart rate associated with anxiety attacks can deprive the brain of oxygen, causing a character to faint.

Fear-Induced Fainting (Vasovagal Syncope): This occurs when a character is so afraid that their body’s fight-or-flight response leads to fainting.

Environmental Causes

Lack of Oxygen: Situations like suffocation, high altitudes, or enclosed spaces with poor ventilation can deprive the brain of oxygen and cause fainting.

Poisoning or Toxins: Certain chemicals or gasses (e.g., carbon monoxide) can interfere with the body’s ability to transport oxygen, leading to unconsciousness.

3. The Stages of Passing Out

To write a realistic fainting scene, it’s important to understand the stages of syncope. Fainting is usually a process, and characters will likely experience several key warning signs before they fully lose consciousness.

Pre-Syncope (The Warning Signs)

Before losing consciousness, a character will typically go through a pre-syncope phase. This period can last anywhere from a few seconds to a couple of minutes, and it’s full of physical indicators that something is wrong.

Light-Headedness and Dizziness: A feeling that the world is spinning, which can be exacerbated by movement.

Blurred or Tunnel Vision: The character may notice their vision narrowing or going dark at the edges.

Ringing in the Ears: Often accompanied by a feeling of pressure or muffled hearing.

Weakness in Limbs: The character may feel unsteady, like their legs can’t support them.

Sweating and Nausea: A sudden onset of cold sweats, clamminess, and nausea is common.

Rapid Heartbeat (Tachycardia): The heart races as it tries to maintain blood flow to the brain.

Syncope (The Loss of Consciousness)

When the character faints, the actual loss of consciousness happens quickly, often within seconds of the pre-syncope signs.

The Body Going Limp: The character will crumple to the ground, usually without the ability to break their fall.

Breathing: Breathing continues, but it may be shallow and rapid.

Pulse: While fainting, the heart rate can either slow down dramatically or remain rapid, depending on the cause.

Duration: Most fainting episodes last from a few seconds to a minute or two. Prolonged unconsciousness may indicate a more serious issue.

Post-Syncope (The Recovery)

After a character regains consciousness, they’ll typically feel groggy and disoriented. This phase can last several minutes.

Disorientation: The character may not immediately remember where they are or what happened.

Lingering Dizziness: Standing up too quickly after fainting can trigger another fainting spell.

Nausea and Headache: After waking up, the character might feel sick or develop a headache.

Weakness: Even after regaining consciousness, the body might feel weak or shaky for several hours.

4. The Physical Effects of Fainting

Fainting isn’t just about losing consciousness—there are physical consequences too. Depending on the circumstances, your character may suffer additional injuries from falling, especially if they hit something on the way down.

Impact on the Body

Falling Injuries: When someone faints, they usually drop straight to the ground, often hitting their head or body in the process. Characters may suffer cuts, bruises, or even broken bones.

Head Injuries: Falling and hitting their head on the floor or a nearby object can lead to concussions or more severe trauma.

Scrapes and Bruises: If your character faints on a rough surface or near furniture, they may sustain scrapes, bruises, or other minor injuries.

Physical Vulnerability

Uncontrolled Fall: The character’s body crumples or falls in a heap. Without the ability to brace themselves, they are at risk for further injuries.

Exposed While Unconscious: While fainted, the character is vulnerable to their surroundings. This could lead to danger in the form of attackers, environmental hazards, or secondary injuries from their immediate environment.

Signs to Look For While Unconscious

Shallow Breathing: The character's breathing will typically become shallow or irregular while they’re unconscious.

Pale or Flushed Skin: Depending on the cause of fainting, a character’s skin may become very pale or flushed.

Twitching or Muscle Spasms: In some cases, fainting can be accompanied by brief muscle spasms or jerking movements.

5. Writing Different Types of Fainting

There are different types of fainting, and each can serve a distinct narrative purpose. The way a character faints can help enhance the scene's tension or emotion.

Sudden Collapse

In this case, the character blacks out without any warning. This type of fainting is often caused by sudden physical trauma or exhaustion.

No Warning: The character simply drops, startling both themselves and those around them.

Used in High-Tension Scenes: For example, a character fighting in a battle may suddenly collapse from blood loss, raising the stakes instantly.

Slow and Gradual Fainting

This happens when a character feels themselves fading, usually due to emotional stress or exhaustion.

Internal Monologue: The character might have time to realize something is wrong and reflect on what’s happening before they lose consciousness.

Adds Suspense: The reader is aware that the character is fading but may not know when they’ll drop.

Dramatic Fainting

Some stories call for a more theatrical faint, especially in genres like historical fiction or period dramas.

Exaggerated Swooning: A character might faint from shock or fear, clutching their chest or forehead before collapsing.

Evokes a Specific Tone: This type of fainting works well for dramatic, soap-opera-like scenes where the fainting is part of the tension.

6. Aftermath: How Characters Feel After Waking Up

When your character wakes up from fainting, they’re not going to bounce back immediately. There are often lingering effects that last for minutes—or even hours.

Physical Recovery

Dizziness and Nausea: Characters might feel off-balance or sick to their stomach when they first come around.

Headaches: A headache is a common symptom post-fainting, especially if the character hits their head.

Body Aches: Muscle weakness or stiffness may persist, especially if the character fainted for a long period or in an awkward position.

Emotional and Mental Impact

Confusion: The character may not remember why they fainted or what happened leading up to the event.

Embarrassment: Depending on the situation, fainting can be humiliating, especially if it happened in front of others.

Fear: Characters who faint from emotional shock might be afraid of fainting again or of the situation that caused it.

7. Writing Tips: Making It Believable

Writing a fainting scene can be tricky. If not handled properly, it can come across as melodramatic or unrealistic. Here are some key tips to ensure your fainting scenes are both believable and impactful.

Understand the Cause

First and foremost, ensure that the cause of fainting makes sense in the context of your story. Characters shouldn’t pass out randomly—there should always be a logical reason for it.

Foreshadow the Fainting: If your character is losing blood, suffering from dehydration, or undergoing extreme emotional stress, give subtle clues that they might pass out. Show their discomfort building before they collapse.

Avoid Overuse: Fainting should be reserved for moments of high stakes or significant plot shifts. Using it too often diminishes its impact.

Balance Realism with Drama

While you want your fainting scene to be dramatic, don’t overdo it. Excessively long or theatrical collapses can feel unrealistic.

Keep It Short: Fainting typically happens fast. Avoid dragging the loss of consciousness out for too long, as it can slow down the pacing of your story.

Don’t Always Save the Character in Time: In some cases, let the character hit the ground. This adds realism, especially if they’re fainting due to an injury or traumatic event.

Consider the Aftermath

Make sure to give attention to what happens after the character faints. This part is often overlooked, but it’s important for maintaining realism and continuity.

Lingering Effects: Mention the character’s disorientation, dizziness, or confusion upon waking up. It’s rare for someone to bounce back immediately after fainting.

Reactions of Others: If other characters are present, how do they react? Are they alarmed? Do they rush to help, or are they unsure how to respond?

Avoid Overly Romanticized Fainting

In some genres, fainting is used as a dramatic or romantic plot device, but this can feel outdated and unrealistic. Try to focus on the genuine physical or emotional toll fainting takes on a character.

Stay Away from Clichés: Avoid having your character faint simply to be saved by a love interest. If there’s a romantic element, make sure it’s woven naturally into the plot rather than feeling forced.

8. Common Misconceptions About Fainting

Fainting is often misrepresented in fiction, with exaggerated symptoms or unrealistic recoveries. Here are some common myths about fainting, and the truth behind them.

Myth 1: Fainting Always Comes Without Warning

While some fainting episodes are sudden, most people experience warning signs (lightheadedness, blurred vision) before passing out. This gives the character a chance to notice something is wrong before losing consciousness.

Myth 2: Fainting Is Dramatic and Slow

In reality, fainting happens quickly—usually within a few seconds of the first warning signs. Characters won’t have time for long speeches or dramatic gestures before collapsing.

Myth 3: Characters Instantly Bounce Back

Many stories show characters waking up and being perfectly fine after fainting, but this is rarely the case. Fainting usually leaves people disoriented, weak, or even nauseous for several minutes afterward.

Myth 4: Fainting Is Harmless

In some cases, fainting can indicate a serious medical issue, like heart problems or severe dehydration. If your character is fainting frequently, it should be addressed in the story as a sign of something more severe.

Looking For More Writing Tips And Tricks?

Are you an author looking for writing tips and tricks to better your manuscript? Or do you want to learn about how to get a literary agent, get published and properly market your book? Consider checking out the rest of Quillology with Haya Sameer; a blog dedicated to writing and publishing tips for authors! While you’re at it, don’t forget to head over to my TikTok and Instagram profiles @hayatheauthor to learn more about my WIP and writing journey!

Perfectly NOT Fine: Chapter 3

BLURB:

Instead of Deepnest, the Knight went up through the City of Tears to escape. What would happen but being found and adopted by none other than the Watcher himself.

Tell me, what happens now? After all, the Knight has a twin in the White Palace down below....

Previous: https://www.tumblr.com/violetdawn001/741443039477858304/perfectly-not-fine-chapter-2?source=share

SCRIPT:

Nothing was the same after that meeting in the White Palace. I told no one, of course, of what the king told me.

Yet that did little to prevent our household from putting facts together that someone threatened the Spire...and you.

You, my son, never noticed the threats. You were so full of excitement from your godmother and all the squires spending all their "free" time with you.

No, not free from duty, for they made loving you their duty.

A choice no one consulted me about.

While our household prepared for what could be, I turned my gaze to what had been...and what to do now.

His Majesty told me of his plans; Of how there were no costs too great...and not to fret for HE would pay them. Pay them with the sweat and blood of his own child. A vessel wearing a dead shell-ha! What a lie to mask the faces of living children! Despite the clear gravity of what His Majesty did and was doing... Dust clouds obscured the best path forward. On One Hand, I stand up to the King, Fight for the King's child, Speak out against this plan. Slighting the Pale King's Dignity and Opening the kingdom to rot. In other words, TREASON. On the Other Hand, I say nothing, do Nothing so that the citizens of the kingdom are saved. Dooming the Princeling to chains and Daming the Pale King to Hell. In conclusion, also TREASON. Strike the Body to save the Soul. Dam the Soul to Save the Body. Any action taken now will be TREASON. Treason, treason, TREASON, TREASON!!! *Soft Footsteps are heard* "?" "Meep! Meep!" I cannot begin to thank you, my son, for bringing me out of that storm. And for the realization of what loyalty I ought to hold most true.

Previous:

https://www.tumblr.com/violetdawn001/741443039477858304/perfectly-not-fine-chapter-2?source=share

Start Here/Cover:

https://www.tumblr.com/violetdawn001/738375072551682048/part-1-prologue?source=share

Next Chapter: Please be patient. 😄

NOTES: Why does Lurien only hire smart people? His servants demanded three extra pages just so they could show how THEY were watching and had to do something!

Okay, this could actually make sense. Also explains how the White Lady could know everything going on in Hallownest.

Alright, here me out...

What if the White Lady is a fungus?

(also have this old artwork I never posted)

Excuse me while I reblog this for future reference...

Words for Skin Tone | How to Describe Skin Color

We discussed the issues describing People of Color by means of food in Part I of this guide, which brought rise to even more questions, mostly along the lines of “So, if food’s not an option, what can I use?” Well, I was just getting to that!

This final portion focuses on describing skin tone, with photo and passage examples provided throughout. I hope to cover everything from the use of straight-forward description to the more creatively-inclined, keeping in mind the questions we’ve received on this topic.

Standard Description

Basic Colors

Pictured above: Black, Brown, Beige, White, Pink.

“She had brown skin.”

This is a perfectly fine description that, while not providing the most detail, works well and will never become cliché.

Describing characters’ skin as simply brown or beige works on its own, though it’s not particularly telling just from the range in brown alone.

Complex Colors

These are more rarely used words that actually “mean” their color. Some of these have multiple meanings, so you’ll want to look into those to determine what other associations a word might have.

Pictured above: Umber, Sepia, Ochre, Russet, Terra-cotta, Gold, Tawny, Taupe, Khaki, Fawn.

Complex colors work well alone, though often pair well with a basic color in regards to narrowing down shade/tone.

For example: Golden brown, russet brown, tawny beige…

As some of these are on the “rare” side, sliding in a definition of the word within the sentence itself may help readers who are unfamiliar with the term visualize the color without seeking a dictionary.

“He was tall and slim, his skin a russet, reddish-brown.”

Comparisons to familiar colors or visuals are also helpful:

“His skin was an ochre color, much like the mellow-brown light that bathed the forest.”

Modifiers

Modifiers, often adjectives, make partial changes to a word.The following words are descriptors in reference to skin tone.

Dark - Deep - Rich - Cool

Warm - Medium - Tan

Fair - Light - Pale

Rich Black, Dark brown, Warm beige, Pale pink…

If you’re looking to get more specific than “brown,” modifiers narrow down shade further.

Keep in mind that these modifiers are not exactly colors.

As an already brown-skinned person, I get tan from a lot of sun and resultingly become a darker, deeper brown. I turn a pale, more yellow-brown in the winter.

While best used in combination with a color, I suppose words like “tan” “fair” and “light” do work alone; just note that tan is less likely to be taken for “naturally tan” and much more likely a tanned White person.

Calling someone “dark” as description on its own is offensive to some and also ambiguous. (See: Describing Skin as Dark)

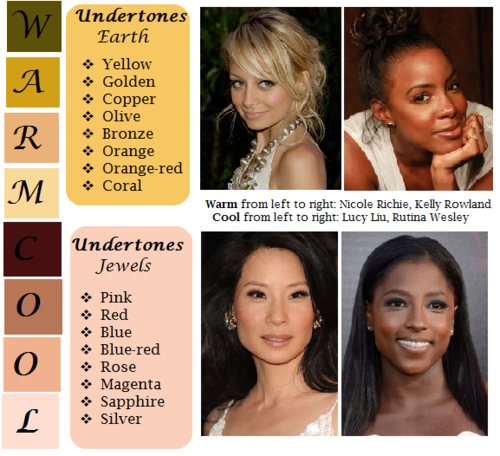

Undertones

Undertones are the colors beneath the skin, seeing as skin isn’t just one even color but has more subdued tones within the dominating palette.

pictured above: warm / earth undertones: yellow, golden, copper, olive, bronze, orange, orange-red, coral | cool / jewel undertones: pink, red, blue, blue-red, rose, magenta, sapphire, silver.

Mentioning the undertones within a character’s skin is an even more precise way to denote skin tone.

As shown, there’s a difference between say, brown skin with warm orange-red undertones (Kelly Rowland) and brown skin with cool, jewel undertones (Rutina Wesley).

“A dazzling smile revealed the bronze glow at her cheeks.”

“He always looked as if he’d ran a mile, a constant tinge of pink under his tawny skin.”

Standard Description Passage

“Farah’s skin, always fawn, had burned and freckled under the summer’s sun. Even at the cusp of autumn, an uneven tan clung to her skin like burrs. So unlike the smooth, red-brown ochre of her mother, which the sun had richened to a blessing.”

-From my story “Where Summer Ends” featured in Strange Little Girls

Here the state of skin also gives insight on character.

Note my use of “fawn” in regards to multiple meaning and association. While fawn is a color, it’s also a small, timid deer, which describes this very traumatized character of mine perfectly.

Though I use standard descriptions of skin tone more in my writing, at the same time I’m no stranger to creative descriptions, and do enjoy the occasional artsy detail of a character.

Creative Description

Whether compared to night-cast rivers or day’s first light…I actually enjoy seeing Characters of Colors dressed in artful detail.

I’ve read loads of descriptions in my day of white characters and their “smooth rose-tinged ivory skin”, while the PoC, if there, are reduced to something from a candy bowl or a Starbucks drink, so to actually read of PoC described in lavish detail can be somewhat of a treat.

Still, be mindful when you get creative with your character descriptions. Too many frills can become purple-prose-like, so do what feels right for your writing when and where. Not every character or scene warrants a creative description, either. Especially if they’re not even a secondary character.

Using a combination of color descriptions from standard to creative is probably a better method than straight creative. But again, do what’s good for your tale.

Natural Settings - Sky

Pictured above: Harvest Moon -Twilight, Fall/Autumn Leaves, Clay, Desert/Sahara, Sunlight - Sunrise - Sunset - Afterglow - Dawn- Day- Daybreak, Field - Prairie - Wheat, Mountain/Cliff, Beach/Sand/Straw/Hay.

Now before you run off to compare your heroine’s skin to the harvest moon or a cliff side, think about the associations to your words.

When I think cliff, I think of jagged, perilous, rough. I hear sand and picture grainy, yet smooth. Calm. mellow.

So consider your character and what you see fit to compare them to.

Also consider whose perspective you’re describing them from. Someone describing a person they revere or admire may have a more pleasant, loftier description than someone who can’t stand the person.

“Her face was like the fire-gold glow of dawn, lifting my gaze, drawing me in.”

“She had a sandy complexion, smooth and tawny.”

Even creative descriptions tend to draw help from your standard words.

Flowers

Pictured above: Calla lilies, Western Coneflower, Hazel Fay, Hibiscus, Freesia, Rose

It was a bit difficult to find flowers to my liking that didn’t have a 20 character name or wasn’t called something like “chocolate silk” so these are the finalists.

You’ll definitely want to avoid purple-prose here.

Also be aware of flowers that most might’ve never heard of. Roses are easy, as most know the look and coloring(s) of this plant. But Western coneflowers? Calla lilies? Maybe not so much.

“He entered the cottage in a huff, cheeks a blushing brown like the flowers Nana planted right under my window. Hazel Fay she called them, was it?”

Assorted Plants & Nature

Pictured above: Cattails, Seashell, Driftwood, Pinecone, Acorn, Amber

These ones are kinda odd. Perhaps because I’ve never seen these in comparison to skin tone, With the exception of amber.

At least they’re common enough that most may have an idea what you’re talking about at the mention of “pinecone.“

I suggest reading out your sentences aloud to get a better feel of how it’ll sounds.

"Auburn hair swept past pointed ears, set around a face like an acorn both in shape and shade.”

I pictured some tree-dwelling being or person from a fantasy world in this example, which makes the comparison more appropriate.

I don’t suggest using a comparison just “cuz you can” but actually being thoughtful about what you’re comparing your character to and how it applies to your character and/or setting.

Wood

Pictured above: Mahogany, Walnut, Chestnut, Golden Oak, Ash

Wood can be an iffy description for skin tone. Not only due to several of them having “foody” terminology within their names, but again, associations.

Some people would prefer not to compare/be compared to wood at all, so get opinions, try it aloud, and make sure it’s appropriate to the character if you do use it.

“The old warlock’s skin was a deep shade of mahogany, his stare serious and firm as it held mine.”

Metals

Pictured above: Platinum, Copper, Brass, Gold, Bronze

Copper skin, brass-colored skin, golden skin…

I’ve even heard variations of these used before by comparison to an object of the same properties/coloring, such as penny for copper.

These also work well with modifiers.

“The dress of fine white silks popped against the deep bronze of her skin.”

Gemstones - Minerals

Pictured above: Onyx, Obsidian, Sard, Topaz, Carnelian, Smoky Quartz, Rutile, Pyrite, Citrine, Gypsum

These are trickier to use. As with some complex colors, the writer will have to get us to understand what most of these look like.

If you use these, or any more rare description, consider if it actually “fits” the book or scene.

Even if you’re able to get us to picture what “rutile” looks like, why are you using this description as opposed to something else? Have that answer for yourself.

“His skin reminded her of the topaz ring her father wore at his finger, a gleaming stone of brown, mellow facades.”

Physical Description

Physical character description can be more than skin tone.

Show us hair, eyes, noses, mouth, hands…body posture, body shape, skin texture… though not necessarily all of those nor at once.

Describing features also helps indicate race, especially if your character has some traits common within the race they are, such as afro hair to a Black character.

How comprehensive you decide to get is up to you. I wouldn’t overdo it and get specific to every mole and birthmark. Noting defining characteristics is good, though, like slightly spaced front teeth, curls that stay flopping in their face, hands freckled with sunspots…

General Tips

Indicate Race Early: I suggest indicators of race be made at the earliest convenience within the writing, with more hints threaded throughout here and there.

Get Creative On Your Own: Obviously, I couldn’t cover every proper color or comparison in which has been “approved” to use for your characters’ skin color, so it’s up to you to use discretion when seeking other ways and shades to describe skin tone.

Skin Color May Not Be Enough: Describing skin tone isn’t always enough to indicate someone’s ethnicity. As timeless cases with readers equating brown to “dark white” or something, more indicators of race may be needed.

Describe White characters and PoC Alike: You should describe the race and/or skin tone of your white characters just as you do your Characters of Color. If you don’t, you risk implying that White is the default human being and PoC are the “Other”).

PSA: Don’t use “Colored.” Based on some asks we’ve received using this word, I’d like to say that unless you or your character is a racist grandmama from the 1960s, do not call People of Color “colored” please.

Not Sure Where to Start? You really can’t go wrong using basic colors for your skin descriptions. It’s actually what many people prefer and works best for most writing. Personally, I tend to describe my characters using a combo of basic colors + modifiers, with mentions of undertones at times. I do like to veer into more creative descriptions on occasion.

Want some alternatives to “skin” or “skin color”? Try: Appearance, blend, blush, cast, coloring, complexion, flush, glow, hue, overtone, palette, pigmentation, rinse, shade, sheen, spectrum, tinge, tint, tone, undertone, value, wash.

Skin Tone Resources

List of Color Names

The Color Thesaurus

Skin Undertone & Color Matching

Tips and Words on Describing Skin

Photos: Undertones Described (Modifiers included)

Online Thesaurus (try colors, such as “red” & “brown”)

Don’t Call me Pastries: Creative Skin Tones w/ pics I

Writing & Description Guides

WWC Featured Description Posts

WWC Guide: Words to Describe Hair

Writing with Color: Description & Skin Color Tags

7 Offensive Mistakes Well-intentioned Writers Make

I tried to be as comprehensive as possible with this guide, but if you have a question regarding describing skin color that hasn’t been answered within part I or II of this guide, or have more questions after reading this post, feel free to ask!

~ Mod Colette

-

jef-jaxon reblogged this · 4 months ago

jef-jaxon reblogged this · 4 months ago -

violetdawn001 reblogged this · 4 months ago

violetdawn001 reblogged this · 4 months ago -

violetdawn001 reblogged this · 4 months ago

violetdawn001 reblogged this · 4 months ago -

violetdawn001 liked this · 4 months ago

violetdawn001 liked this · 4 months ago -

jef-jaxon reblogged this · 5 years ago

jef-jaxon reblogged this · 5 years ago