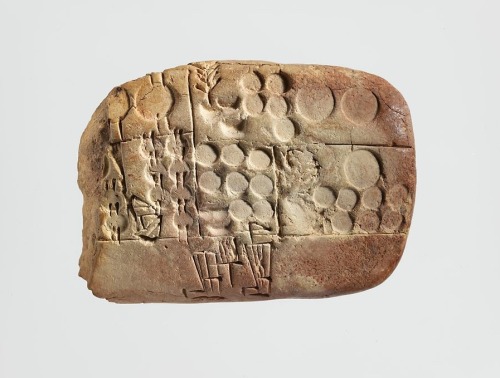

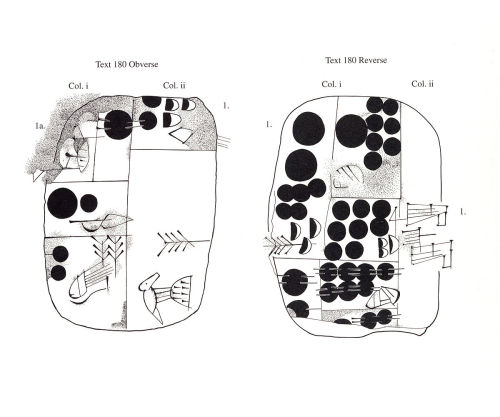

Sumerian Cuneiform Tablet (c. 3100 – 2900 BC). Administrative Account Recording The Distribution

Sumerian cuneiform tablet (c. 3100 – 2900 BC). Administrative account recording the distribution of barley and emmer wheat. Probably from Uruk (Warka, Iraq).

The first system of writing in the world was developed by the Sumerians, beginning c. 3500 – 3000 BC. It was the most significant of Sumer’s cultural contributions, and much of this development happened in the city of Uruk.

A stylus was used to creat wedge-like impresssions in soft clay, and the clay was fired afterwards. The word “cuneiform” comes from the Latin cuneus, meaning “wedge”.

These wedge-like impressions were first pictographs, and later on phonograms (symbols representing vocal sounds) and “word-concepts” – closer to a modern-day understanding of words and writing. All the great Mesopotamian civilizations used cuneiform, including the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Hatti, Hittites, Assyrians and Hurrians. Around 100 BC, it was abandoned in favour of the alphabetic script.

The earliest texts used proto-cuneiform, and were pictorial. Writing was a technique for noting down things, items and objects (e.g. Two Sheep Temple God Inanna). This system worked well for concrete, visible subjects, but could give little in the way of details. As subject matter became more intangible (e.g. the will of the gods, the quest for immortality), cuneiform developed in complexity to represent this.

By 3000 BC, the representations were more simplified. The stylus’ impressions conveyed word-concepts rather than word-signs – for example, the scribe could write about the more abstract concept of “honour”, rather than having to specifically depict “an honourable man”.

The “rebus” principle was used to isolate the phonetic (sound) value of a particular sign. Rebus is a device that combines pictures (or pictographs) with individual letters to depict words and/or phrases. For example, the picture of a bumblebee followed by the letter “n” would represent the word “been”. With the rebus principle, scribes could express grammatical relationships and syntax to clarify meaning and be more precise.

There are only a few examples of the use of rebus in the earliest stages of cuneiform (c. 3200 – 3000 BC). Consistent usage of rebus became apparent only after c. 2600 BC. This was the beginning of a true writing system, characterized by a complex combination of word signs and phonograms (signs for vowels and syllables).

By c. 2500 BC, cuneiform (written mostly on clay tablets) was used for a wide variety of religious, political, literary, scholarly and economic documents.

Now the reader of the tablet didn’t have to struggle with the meaning of a pictograph – they could read word-concepts that more clearly conveyed the scribe’s meaning. The number of characters used in writing was reduced from 1000 to 600, to make it simpler.

By the time of the famous priestess-poet Enheduanna (c. 2285 – 2250 BC), cuneiform had become sophisticated enough to convey not only emotional states such as love or betrayal, but also the reasons behind the writer’s experience of these states. Enheduanna wrote a collection of hymns to Inanna in the Sumerian city of Ur, and she is the first author in the world known by name.

More Posts from Absiesfeed and Others

Gravitational View #02

Yigal Pardo

Color has been disappearing from the world.

A new research group used machine learning to track color changes in common materials and items, below is their findings for all color changes over time, they used 7000+ items from the 1800s to now to determine color changes in the most common items.

Below are the colors of cars by year, notice how the majority of cars are grey, white, or black compared to twenty years ago.

These aren't data points, but they are comparisons between the 'modern' homes of the 70s and 80s compared to the modern homes of today.

Carpets have equally had the same treatment of grey added to them! The most common color of carpet is now grey or beige.

Even locations that used to scream with color for decades have now modernized to becoming boring minimalist (and I love minimalism) personality-less locations.

The world is becoming colorless, why?

source paper

“I want to write books that unlock the traffic jam in everybody’s head.”

— John Updike, Hugging the Shore

Stories of Your Life and Others - Ted Chiang

A book review by Danny Yee

© 2011 https://dannyreviews.com/

The stories in Stories of Your Life and Others tackle big ideas intelligently, in the grand tradition of science fiction. They postulate some fundamental change in how the world works and explore its implications through the experiences or challenges faced by their protagonists.

"Tower of Babylon" is set in a Mesopotamia where there really is a vault of heaven for a tower to reach. In "Understand" an experimental drug makes the protagonist really, really intelligent, capable of understanding not only the world but his own mind. And "Division by Zero" is about a mathematician who discovers that arithmetic is inconsistent.

In "Story of Your Life" a linguist is drafted to help decipher the language of heptapod aliens. Interspersed with the narrative of her linguistic discoveries are vignettes of her lifetime relationship with her daughter. At first these two strands appear to have no connection at all — and their link turns out to be indirect, involving variational approaches to physics and a different kind of consciousness, challenging our notions of memory and free will.

"Seventy-Two Letters" is set in a 19th century England where industrialisation is kabbalah-inspired, with automata (golems) manufactured by applying names to sculptures. And reproduction works in accordance with preformationist theory, with tiny homunculi recursively nested inside sperm. This is mixed up with some politics, involving eugenics and class tensions, and some action. "The Evolution of Human Science", originally published in Nature, is less a story than an abstract speculation about how human science might react to a "metahuman" population with a superior but incommunicable knowledge system.

In "Hell is the Absence of God" angels regularly visit the earth, dealing out miracles (and incidental damage); statistics are kept on the results, and on the fraction of people who are taken to Heaven or condemned to life in Hell, without God. The lead character is desperate to learn how to love God so he can rejoin his dead wife in Heaven; two other characters face rather different challenges.

Presented in a documentary format, with short perspectives from different people, "Liking What You See" is set in a near future where it's possible to reversibly modify people's brains so that they don't perceive beauty or ugliness in faces. A progressive university is debating whether this, known as calliagnosia, should be a requirement for students.The significant novelties involved in Chiang's stories require some serious suspension of disbelief, but he manages this well. He doesn't dwell on the presuppositions or back-story, attempting to justify the impossible, but rapidly introduces the setting and elaborates on it only as much as is necessary for the plot and the exploration of ideas. (The occasional exceptions are jarring, for example in "Story of Your Life" when some nonsensical argument is presented to explain why the aliens haven't learned anything from human television broadcasts.)

None of the characters have much depth. They are driven by intellect rather than emotion and their personalities presented from the outside, fairly clinically. A focus on their understanding of the world is arguably necessary for the elaboration of the story ideas, however, and there's only so much that can be fitted into a short story. (I am not convinced that Chiang could produce a decent novel using the same approach.)The plots work effectively, both in unfolding the implications of the central ideas and in holding the reader's attention. This is true both in the stories with straightforward chronological narratives and in the more unusually structured ones, with resolutions provided by a mix of goal seeking, problem solution, and structural cadence.Stories of Your Life and Others is the most entertaining and thought-provoking collection of science fiction stories I've read for a long time.

Cimitero di San Cataldo | Modena | Aldo Rossi/ Gianni Braghieri | 1984

تم مجھے روزقیامت ملنا،

تم سے میرا حساب باکی ہے۔

Tum mujhe roz-e-qayamat milna,

Tum se mera hisab baaki hai.

~Lines

Desi LGBT Fest 2023 (hosted by @desi-lgbt-fest)

Day 7 : Faith/Rituals of Love

Definitely geared heavily towards the 'Faith' part of this prompt as soon as I read it!

If being Queer is defying conventions and if being a part of the Queer community means going against heteronormativity and gender conformity, is it not Queer to forego materialistic ties and the love of a human partner and embrace the love of a greater being you have only heard about in stories?

All four individuals featured here were integral part of the Bhakti Movement and/or Sufism in South Asia. None were married other than Meerabai.

(Panel order from top to bottom)

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486-1534) : A key name of the Bhakti Movement and the Gauriya Vaishnav tradition in 15th Century Bengal, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu was believed to have been a vessel for both Radha and Krishna. Bengali doesn't use pronouns or gendered language and we may never know what they would have preferred to be identified as in a language they didn't know (English), I will simply resort to using They/Them for them. Their written teachings are few and far between but the verse mentioned here is the seventh verse of the only written record of their teachings, the Shikshastakam - a collection of 8 total verses. The translation here is my own and quite literal so that the interpretation is left to the reader.

Meerabai (1498-1597) : [CW : IMPLIED QUEERPHOBIA/APHOBIA] Meerabai was born into Rajput royalty and was married off, also to Rajput royalty, in likely an arranged marriage. While most of the stories surrounding her are folklore whose historicity is yet to be confirmed, her marital status can be confirmed, and so can her devotion and affection for Krishna and the divine, which she has herself penned in numerous poems and songs. Folklore does strongly imply that she was non-committal to her marriage and that her in-laws tried to poison her to death multiple times for it.

Kabir (1398–1448 or 1440–1518) : Found as an orphan by a Muslim weaver couple, Kabir's religion grew to become somewhat of an enigma for future generations. His stance, however, on the topic romance and marital relationships is quite clear - he looked down upon them and a huge chunk of his couplets strongly imply that romantic and sexual relations simply obstruct spiritual enlightenment.

Bulleh Shah (1680-1757) : Bulleh Shah, though an ardent proponent of loving the divine, was declared a Kafir, a non-believer/non-Muslim by a quite a few Muslim clerics of the time. He was known for speaking up against existing power hierarchies of the time and used vernacular speech for his writings (Punjabi, Sindhi) which not only served to popularize his works, but also let people connect to his words.

A personal note on my motivations under the cut.

A while back when I was actively going through the anxiety of finding out that I am ace and that I will never fit into the current South Asian society that the wedding industry has a chokehold on, I desperately wanted to see people from my own culture living happily without a partner. During one of my history rabbit hole escapedes, I restumbled upon the story of Meerabai, how she always insisted on loving and devoting herself towards Krishna, despite being married into a normative and wealthy household and despite her in-laws repeatedly attempting to poison her for not committing to her husband. Most of us from India grow up hearing about Meerabai, her spiritual connections to Krishna, and her struggles. The moral of those stories is always framed as 'believe in god, he will help you through tough times'. But this was the first time I was making a different connection, I was drawing different morals. And when I took Meerabai's non-conformity to her married life and started looking for more examples like hers, I was overwhelmed by how many more individuals existed without a partner, condemned being in a normative, married relationship, admitted to having lost human connections and faced resistance even, and yet stayed true to their orientation and sounded HAPPY! It was extremely hard to narrow it down to these four, but these do make my point! Labels are hard to transpose across cultures and history. But if being queer means being nonconforming of marital structures and being aspec/arospec implies neutrality, indifference, or aversion to romance and intercourse, then no one fits the label if they don't.

Bearth Deplazes - Schweizer-Schmid house, Ardez 2018. Photos © Gion von Albertini.

I laughed way too hard at this

Wo itefaq se rasty mai mil jaye kahi,

Bs isi shoq ne hume Awara bana dia hai.

~JAUN ELIYA

-

sadeer84 liked this · 5 months ago

sadeer84 liked this · 5 months ago -

lanternhiraeth reblogged this · 1 year ago

lanternhiraeth reblogged this · 1 year ago -

lanternhiraeth liked this · 1 year ago

lanternhiraeth liked this · 1 year ago -

suraanahita liked this · 2 years ago

suraanahita liked this · 2 years ago -

victusinveritas reblogged this · 2 years ago

victusinveritas reblogged this · 2 years ago -

coolancientstuff reblogged this · 2 years ago

coolancientstuff reblogged this · 2 years ago -

ritathememermaid liked this · 2 years ago

ritathememermaid liked this · 2 years ago -

totallyswanky liked this · 2 years ago

totallyswanky liked this · 2 years ago -

miscellaneous-art liked this · 3 years ago

miscellaneous-art liked this · 3 years ago -

feminempreg liked this · 3 years ago

feminempreg liked this · 3 years ago -

fatjack03 liked this · 3 years ago

fatjack03 liked this · 3 years ago -

onemoretime reblogged this · 3 years ago

onemoretime reblogged this · 3 years ago -

rubaduckie32 liked this · 3 years ago

rubaduckie32 liked this · 3 years ago -

careful-disorder liked this · 3 years ago

careful-disorder liked this · 3 years ago -

felizdelavidasblog liked this · 3 years ago

felizdelavidasblog liked this · 3 years ago -

lovingengineerturtle liked this · 3 years ago

lovingengineerturtle liked this · 3 years ago -

dharmabumnamedshasta liked this · 3 years ago

dharmabumnamedshasta liked this · 3 years ago -

barbariankingdom liked this · 3 years ago

barbariankingdom liked this · 3 years ago -

freiherr-von-naarenburg reblogged this · 3 years ago

freiherr-von-naarenburg reblogged this · 3 years ago -

angelsbymoonlight reblogged this · 3 years ago

angelsbymoonlight reblogged this · 3 years ago -

chcherryohbaby reblogged this · 3 years ago

chcherryohbaby reblogged this · 3 years ago -

grumble-all-you-like reblogged this · 3 years ago

grumble-all-you-like reblogged this · 3 years ago -

imperturbitude liked this · 3 years ago

imperturbitude liked this · 3 years ago -

inksmearedhands reblogged this · 3 years ago

inksmearedhands reblogged this · 3 years ago -

halfseafog reblogged this · 3 years ago

halfseafog reblogged this · 3 years ago -

absiesfeed reblogged this · 3 years ago

absiesfeed reblogged this · 3 years ago -

absiesfeed liked this · 3 years ago

absiesfeed liked this · 3 years ago -

leightons-s liked this · 3 years ago

leightons-s liked this · 3 years ago -

shkayy liked this · 3 years ago

shkayy liked this · 3 years ago -

thecrankyprofessor liked this · 3 years ago

thecrankyprofessor liked this · 3 years ago -

latsprec-blog liked this · 3 years ago

latsprec-blog liked this · 3 years ago -

nnurl liked this · 3 years ago

nnurl liked this · 3 years ago -

utah61 liked this · 3 years ago

utah61 liked this · 3 years ago -

moralwounds liked this · 3 years ago

moralwounds liked this · 3 years ago -

thesorcererandhisking liked this · 3 years ago

thesorcererandhisking liked this · 3 years ago -

string-nocturne liked this · 3 years ago

string-nocturne liked this · 3 years ago -

clouseplayssims liked this · 3 years ago

clouseplayssims liked this · 3 years ago -

lisashaverdi reblogged this · 3 years ago

lisashaverdi reblogged this · 3 years ago -

lisashaverdi liked this · 3 years ago

lisashaverdi liked this · 3 years ago